Imposible to Tell

"Hector Hernandez and Robert Jackson Harrington Impossible to Tell" at grayDUCK Gallery

This exhibition's plastic hues and triumphant assemblages convey the belligerent optimism of American-style consumerism

REVIEWED BY SETH ORION SCHWAIGER, JAN. 1, 2016

This is the perfect weekend to see Robert Jackson Harrington and Hector Hernandez's "Impossible to Tell." While we're still nursing the hangover from our annual Christmas consumerist binge (and another kind of hangover from New Year's Eve), and as we enter 2016 with all the unfounded hopes for a better cycle, the atmosphere of this exhibition makes the most sense. The brightly colored photographs and assemblage sculpture built from mostly newly purchased tools and other items (some still with price tags) invoke a quintessentially American air of victory and pride. Here, though, that patriotism takes a strange form with tokens of low-level labor (think mop heads and utility lights) and a color palette deeply informed by current marketing strategy. Even without the American flags poking out the back of several sculptures like battle banners, few could miss the unspoken chant of "USA, USA" filling the gallery, or maybe just simply, "'Merica!"

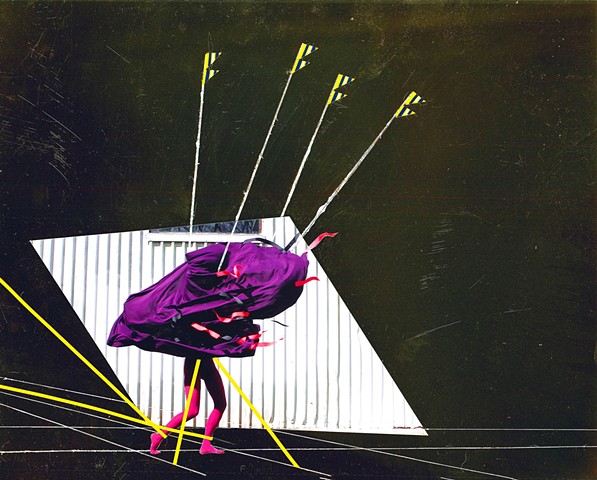

In this exhibition, the aesthetics of current-day labor and manufacturing are torn from their contexts of utility and veer surprisingly pop: harshly saturated, high-visibility oranges, pinks, and greens, coupled with vacuformed glossy plastic casings, shrink wraps, and graphic-heavy cardboards. It's far from the monochromed, oil-stained images of industry found in our collective memory, but a much more accurate depiction of the current state of things, that is, the defusing of simple, childlike marketing strategies toward an increasingly broad do-it-yourself demographic, a demographic previously dominated by unadulterated machismo.

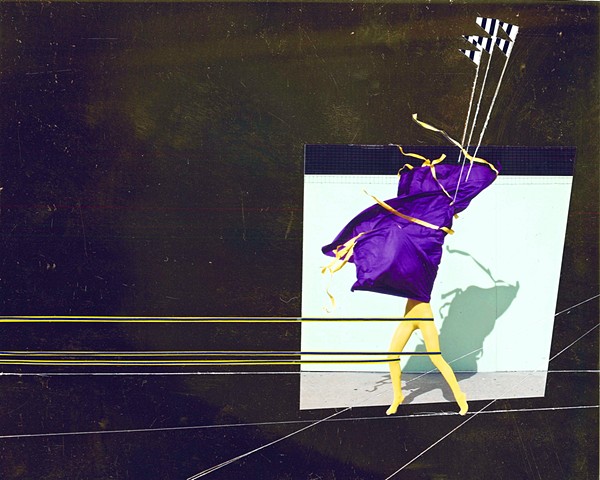

Both artists stick to their own patterns quite closely, but of the two, Harrington seems to take greater risks, testing his limits and creating works that, though consistent in style, vary considerably in scale and form. Hernandez's practice is more narrow and risks coming across as following the same recipe ad infinitum (stage a model in brightly colored tights in the center of the composition in an industrial environment, hide the upper body and head with a whimsical, brightly colored constructed shape or cloth, photograph, repeat). The strongest of his works move furthest away from that formula, such as Never the Machine Forever, in which the model is altered in a more thorough and interesting way, or Sun Shower with its painted-over graffiti in the background, building a dynamic composition and layered concept.

The best works in the show, however, are collaborative, a fact that makes sense in light of the two artists' frequent curatorial endeavors as members of artist collective Los Outsiders – their greatest strengths come from unity and working with other creatives. These collaborative works tie Harrington's machinelike sculptures and material eccentricity to Hernandez's ability to animate unique characters and focus the viewer's attention. In this way, photographs become more engaging with additional beguiling props and collage added to the standard mix. On the other side, the largest assembled sculptures become oddly human, like worker robots ready to colonize (and maybe destroy) whatever's put in front of them.

Potential energies of all sorts dominate the show, from the optimistic USA hurrah founded more on what could be than what has been to direct physical manifestations. Hernandez's figures are frequently caught in midstep, and Harrington's constructions are in some instances even plugged into wall sockets without practical reason. Even the placement of works precariously close to the pedestals' edge helps to build that energy. This conjured sense of suspended action and anticipation is a unique success of the exhibition and one worth spending time with – even through the sharp soberness of the first day of the year.